Part of the PublicSource series

Failing the Future

This fall was supposed to be a dream-come-true football season for the Sto-Rox Vikings. They would charge across new turf at their high school stadium instead of the rugged, rutted grass field that teams have played on for decades.

An alumni fundraising effort had hit its $600,000 goal near the end of the school year. Work was set to start on the new turf in July and games would be played there in September. No longer would the high school players have to maneuver around humps and hollows that could turn ankles and break bones.

But then came the announcement by coach LaRoi Johnson in late June that the amount raised fell about $100,000 short of the cost to install the turf. It would be delayed another year while fundraising resumed.

“They led us on and then they just snatched it away from us,” said Drey Frenzley, a senior who plays defensive tackle.

For Drey, 17, it was just one more example of how the adult world disappoints students in the Sto-Rox School District.

“It happens all the time,” he said.

Members of the Sto-Rox football team run across the school's football field in June.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)In mid-June, he and teammate Eric Wilson, a junior and team quarterback, spoke of how the turf would literally and figuratively level the playing field with their peers. “We’re gonna feel like we are as good as the other schools,” Eric had said.

That feeling, now dissipated, was going to be a big deal. It’s not often that students at Sto-Rox Junior-Senior High School get to feel as worthy as their peers in better-resourced districts. In fact, according to Drey, they are “used to being on the short end of the stick.”

Roughly 480 students attend class in the junior-senior high school — a building that hasn’t been renovated in decades, where the roof leaks, water stains the ceilings and the temperature soars to sweltering levels on warm days.

The school’s Wi-Fi is inconsistent. Students are used to reading novels, like the Sherlock Holmes series, printed from the internet because students and teachers said the district can’t afford to buy books. High school Principal Tim Beck said he was unaware the students didn’t have novels and he ordered them for this school year.

They work with paper and pencil far more often than computers, have a library but no librarian — because her schedule is filled teaching other classes — and have TV production equipment but no one to teach the class.

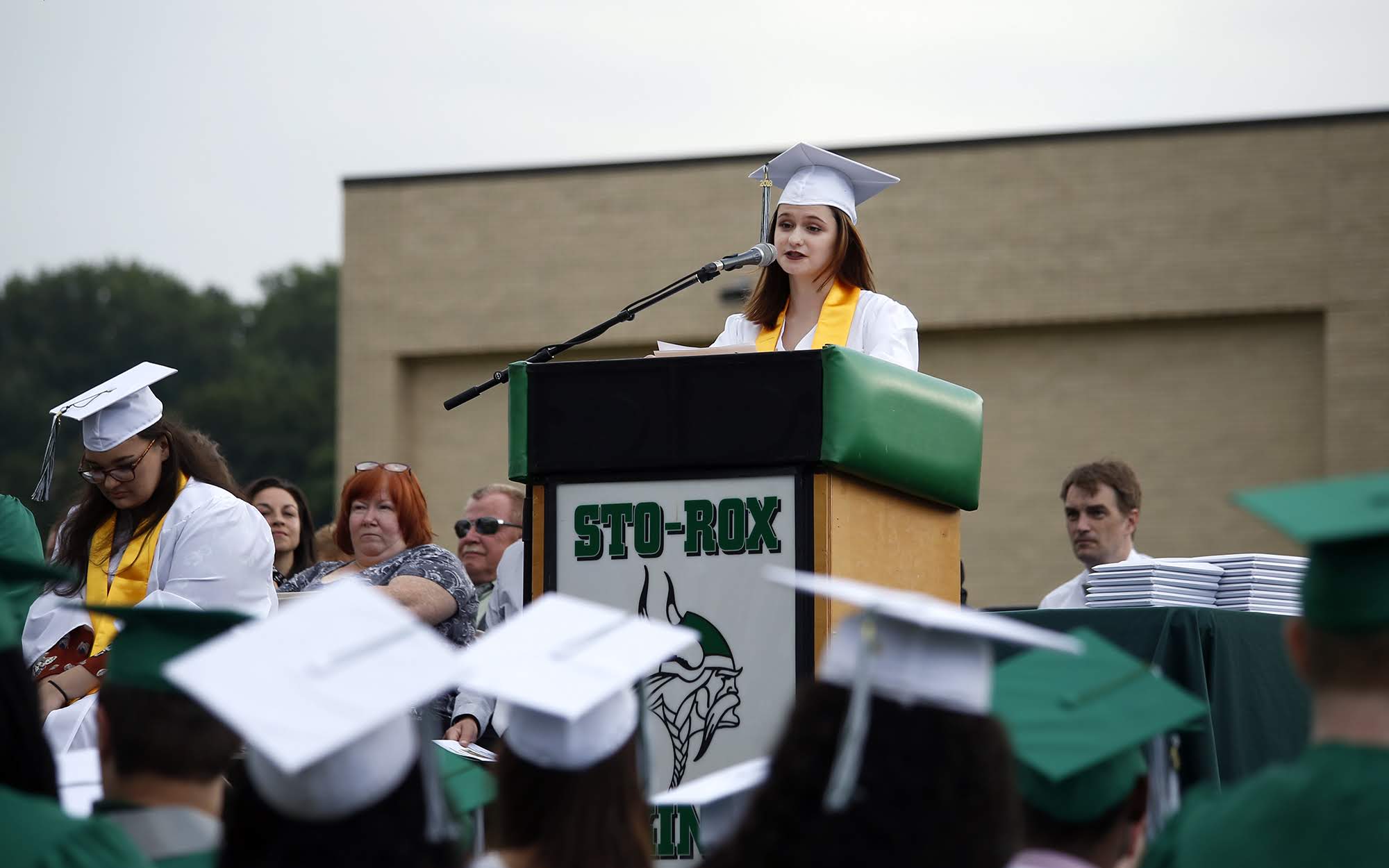

“We’ve learned to live without a lot,” Cassandra Cropper, the Sto-Rox 2018 class salutatorian explained to a reporter last fall. Her comments came at the start of a PublicSource project aimed at documenting disparities between school districts in Southwestern Pennsylvania.

Cassandra Cropper, the Sto-Rox 2018 class salutatorian, says that while Sto-Rox lacks the resources of nearby Montour High School, she and her classmates make do with what they have. It’s a frustrating scenario, Cassandra says, but she still feels she’s received a good education at Sto-Rox. She plans to attend the University of Pittsburgh.

(Video by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)Those disparities are at the heart of a Commonwealth Court lawsuit, claiming that the state’s system of funding schools creates significant inequities among districts because it relies so heavily on local tax revenue. The lawsuit calls for the state to change the way it funds schools.

Initially dismissed by Commonwealth Court, the plaintiffs appealed to the state Supreme Court. In September 2017 the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ordered the case back to Commonwealth Court to hold a trial on whether state officials are violating the state’s Constitution.

Following the ruling, some students, staff and parents in the Sto-Rox district agreed to share their thoughts and experiences over the course of the 2017-18 school year with PublicSource journalists. They provided insight into how the funding system leaves them struggling for access to such basics as textbooks, technology and school staff.

Daily life at Sto-Rox Junior-Senior High School (clockwise): During a lunch period in December 2017, students Taylor Clifford (left) and Leila Quiroz share headphones. A student passes some hallway art. Principal Tim Beck communicates via handheld radio. Students Tyson Peterson (left) and Will Johnson watch as fellow students play basketball, also in December 2017. (Photos by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

(Photos by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)It became quickly apparent that the students, though they don’t fully understand the complexities of school funding, know their district comes up perpetually and painfully short. That means they do without many of the experiences and opportunities extended to students in other schools.

They accept it as a fact of life.

“It’s because we don’t have enough money. I think it’s just the area we live in. It just doesn’t get enough funding,” said Lexi Frazee, another 2018 Sto-Rox graduate who was a star basketball player and honors student. She will attend Slippery Rock University this fall.

Cassandra, Lexi and their classmates were aware that 3 miles up the hill at Montour High School students live a different reality — one where they have their own district-issued Chromebooks and attend school in a sprawling building that recently underwent a $50 million renovation. The school holds a coffee shop, art gallery and empathy room, a quiet place with couches where students can talk and post messages encouraging acts of kindness on the wall.

Students from the Sto-Rox School District are often misunderstood, says Lexi Frazee, a 2018 Sto-Rox graduate. They’re judged by where they grow up. But such assumptions are wrong, she says. Students here have G.R.I.T., which Lexi says stands for Guts, Resilience, Integrity and Tendency. “We are who we are,” she says.

(Video by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)Despite numerous requests from PublicSource, Montour Superintendent Christopher Stone would not answer questions about disparities between his district and Sto-Rox or any efforts Montour takes to help its downhill neighbor.

In his “End of Year Accomplishments” letter, Stone boasted of hosting 100 different tours from visiting school officials interested in Montour’s STEAM and technology facilities, and of articles about the district published in Forbes, Education Week, the Huffington Post and other national and local news sites.

In July, the district announced it would open a 3,000-square-foot artificial intelligence classroom at David E. Williams Middle School.

While there are no consistent partnerships between Montour or Sto-Rox or sharing of resources, Sto-Rox has received advice on writing grant proposals for STEAM funding from Justin Aglio, Montour’s director of academic achievement K-4 and district innovation.

“He was gracious enough to come to me and discuss what I needed to do and helpful ideas, especially with regard to grant partners,” Principal Beck said. Aglio also introduced Beck to officials of the Carnegie Science Center and Remake Learning initiative for future partnerships on STEAM projects.

Inside the Brick Makerspace—a room filled with Legos and other building materials and equipment at Montour Elementary—students Joslin Heckathorne (left), Emma Mcmahon (center) and Brynn Kaczmarek build a car with Legos on Feb. 22, 2018.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

At Montour High School’s empathy room, students have a quiet place with couches where they can talk and post messages encouraging acts of kindness on the wall.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

Justin Aglio, Montour’s director of academic achievement K-4 and district innovation, holds Legos as he speaks prior to the grand opening of the Brick Makerspace, a room filled with Legos and other building materials and equipment at the new Montour Elementary.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)While disparities exist among school districts across the state, it’s hard to find a divide more glaring than the one between the Sto-Rox and Montour school districts.

The gaps don’t end with facilities and supplies.

At Montour, more than 80 percent of the students scored either proficient or advanced on the Keystone Exams in algebra I, literature and biology. At Sto-Rox, 30 percent of students scored proficient or advanced in algebra, 36 percent in literature and 19 percent in biology.

Third-grade reading scores are also widely disparate with 77 percent of Montour students scoring proficient or advanced compared to 22 percent of Sto-Rox students. Third-grade reading scores are significant to a child’s academic success because third grade marks the transition from learning to read and reading to learn.

In 2016-17, Sto-Rox Junior-Senior High School, which holds grades 7-12, also earned the lowest state performance score of middle and high schools among the 42 suburban school districts in Allegheny County. Its School Performance Profile score of 41.5 is based on a scale of 107. Montour High School’s score was 78.1 for grades 9-12. David E. Williams Middle School, with grades 5-8 in Montour, had a score of 78.9.

Socioeconomics and funding

The difference in the school systems is directly related to the socioeconomics of the communities that make up the districts.

According to the state Department of Education, 79 percent of the about 1,300 Sto-Rox students were economically disadvantaged in 2016-17 compared with 28 percent of Montour’s 2,900 students.

Related: Is Pennsylvania’s school funding unfair? This lawsuit hopes to upend the model.

There are differences in racial makeup as well. In Sto-Rox, 52 percent of the students are black. In Montour, 5.5 percent of those enrolled are black.

In Stowe Township, one of two communities that compose the Sto-Rox district, nearly half of the individuals younger than 18 live below the poverty line. In McKees Rocks, the other municipality in the district, 40 percent of its youth live in poverty, according to U.S. Census .

Those rates in Robinson and Kennedy townships — the two largest communities in the Montour district — are 7.5 percent and 5.2 percent, respectively.

Five public housing projects in the Sto-Rox district don’t bring in real estate tax revenue. The area is nearly void of industry or significant retail development.

Robinson, however, is the home of The Mall at Robinson, which sends substantial property tax revenue to the Montour district. In 2017, the mall was assessed at about $92 million, netting a tax yield of $1.6 million.

So when it comes to the ability to raise local revenue for their school districts, here’s how it breaks down: A mill of taxes in Sto-Rox yields about $307,000. A mill of taxes in Montour reaps $2.7 million. (One mill of taxes equals $1 for each $1,000 of assessed real estate value.)

It’s not difficult to see why Montour has been able to catapult its district into the future while the Sto-Rox schools are struggling to maintain status quo.

What’s missing

It’s a dreary Friday in November. A handful of Sto-Rox high school students are gathered in the guidance office – the place they typically go to work on college applications. But on this day, they’re more interested in offering their views on the school’s shortcomings.

Lexi noted her literature class recently got copies of “The Canterbury Tales.” “This is the first time we all got a real book,” she said.

More often, students read materials printed off of the internet, a tedious exercise in the eyes of Davonte Williams, then a senior.

“There are words cut off and it’s faded. I would rather be reading out of a real book,” Davonte said.

English teacher Christopher Captline, head teacher at the high school, explained he prints out Sherlock Holmes stories for students because they are free.

“If there’s an online text and it’s free, I’m gonna use it,” Captline said.

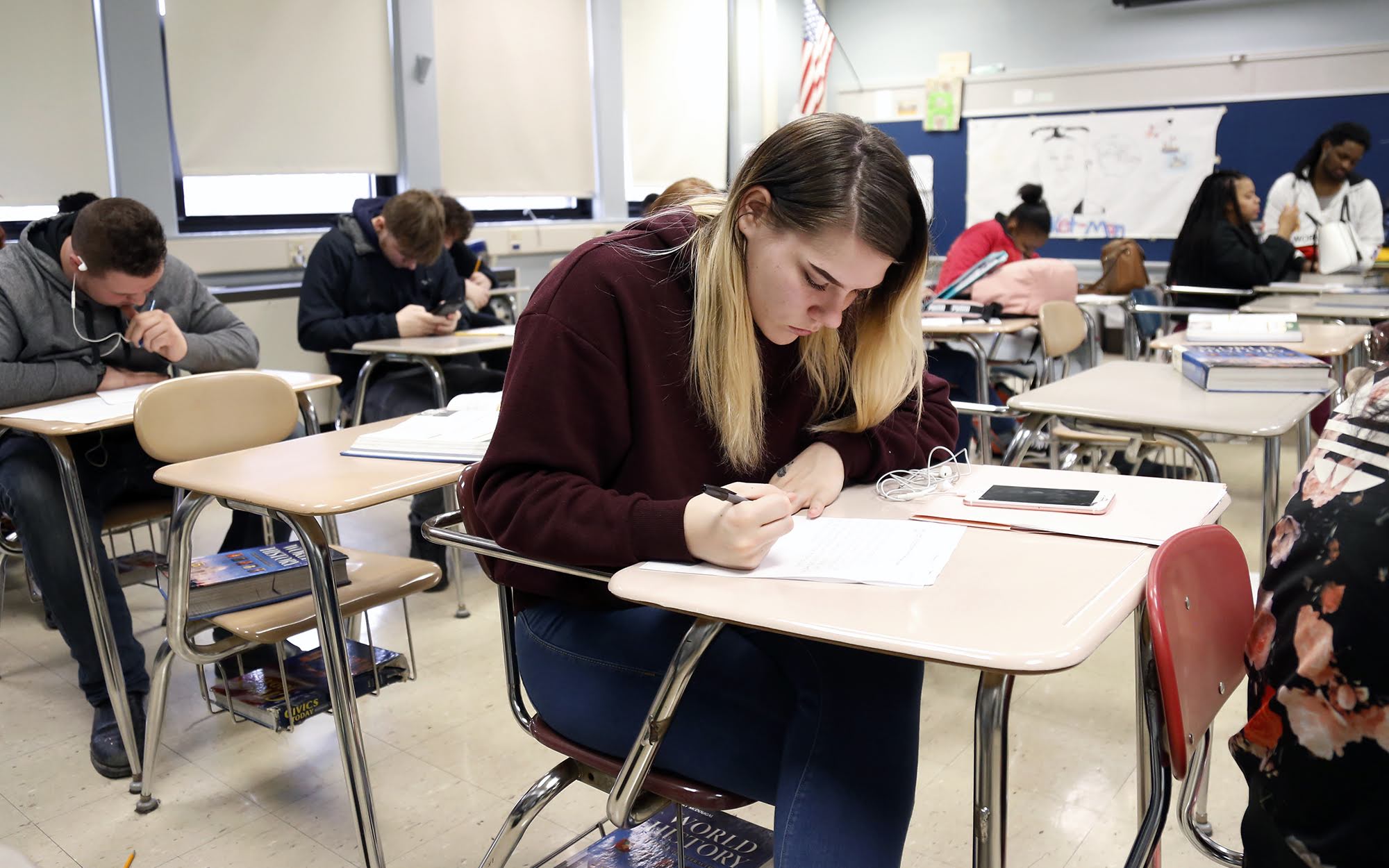

In March, Sto-Rox Junior-Senior High School student Lexi Frazee works in a comparative religions class.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)He can’t use contemporary novels in his classes because there is no money to buy them.

Captline feels badly about that. “There’s nothing like holding a book in your hand,” he said.

Davonte, who was a leading rusher for the the 2017 Sto-Rox football team, listed other things students at his high school were missing. “We don’t have a swimming pool, no track team, no clubs. Lots of kids don’t know how to swim,” Davonte said.

Foreign language offerings include Spanish I and II each year. Spanish III and IV used to be offered, but were later combined into one class and then cut completely because too few students enrolled, Beck said. Spanish teacher Ben Engelhard was then assigned a period supervising Keystone remediation. Two levels of French are offered, but only one level each year. There is only enough room in the schedule to offer one section of the language at a time.

Students don’t have full access to career and technical education, like other districts do. Last school year, about 10 percent of the high school students — 45 students — attended the Parkway West Career and Technical Center, which takes students from from other school districts in grades 9-12. But because Sto-Rox can’t afford to pay the $6,500 annual tuition per student for all four years, its students can’t start until 10th grade, Beck said.

For school safety, the Montour board recently approved adding an armed officer to each school building. Sto-Rox can’t afford any officers. Dean of Students Sam Weaver said he tries to stay in contact with Stowe police about their needs.

Davonte Williams, photographed during his senior year at Sto-Rox Junior-Senior High School.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

Sam Weaver is the dean of students for the Sto-Rox Junior-Senior High School. For safety purposes, Weaver drives the perimeter of the school at dismissal time (pictured on May 24, 2018).

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

Cassandra Cropper, the Sto-Rox 2018 class salutatorian, delivers remarks at the high school's graduation ceremony on June 1, 2018.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

Family members and friends cheer as students participate in Sto-Rox's graduation ceremony on June 1, 2018.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)The school districts appear to have similar levels of incidents involving law enforcement and other misconduct during the 2016-17 school year, according to the state Safe Schools report. But some Sto-Rox incidents were more serious than those in Montour, including reports of five aggravated assaults on staff, four aggravated assaults on students and five threats to school officials or students.

And, in April 2016, a 17-year-old Sto-Rox student was shot in the arm when leaving school at dismissal time.

In conversation, it’s common to hear Sto-Rox students say that not having much helps them to build resilience — a message they hear from teachers and others. But, at times, the students appear more resigned than resilient.

State Education Secretary Pedro Rivera told PublicSource he wants Sto-Rox students to know that he is fighting to get more funding for districts like theirs.

“It’s sad that students start to condition themselves to accepting the fact that they are getting less and will be getting less than neighbors that are sometimes yards away and it saddens me that they feel that way,” Rivera said.

“We always have to ask, ‘Is there money for buses?’”

Sto-Rox students have given up on things like having a high school musical. There’s no money in the budget, and they can’t use the auditorium stage because the overhead curtain pulleys and ropes have been condemned for use because of their age.

At Montour, students last year staged the musical “Once Upon a Mattress.” Before the performance, the cast and crew took a trip to New York City to attend a Broadway play and attended the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust’s theater arts workshop to learn about hair and makeup, movement for actors, scenic design and directing, according to the musical’s Twitter feed.

Montour officials did not release a full budget for its musical, saying it is operated by the outside organization Montour Friends for the Performing Arts. In response to a Right-to-Know Law request for musical costs, the district indicated it donated $7,000 to the musical and paid $100 total for 30 students to attend the theater arts workshop. In response to follow-up questions, the district also revealed it paid a stipend of $3,025 to the musical director.

In Sto-Rox, the first consideration for any field trip, even local, is the cost of transportation. “We always have to ask, ‘Is there money for buses?’” Superintendent Frank Dalmas said. And sometimes students have to pay. For a bus trip to visit a college campus, students were charged $5 to cover costs.

Band class

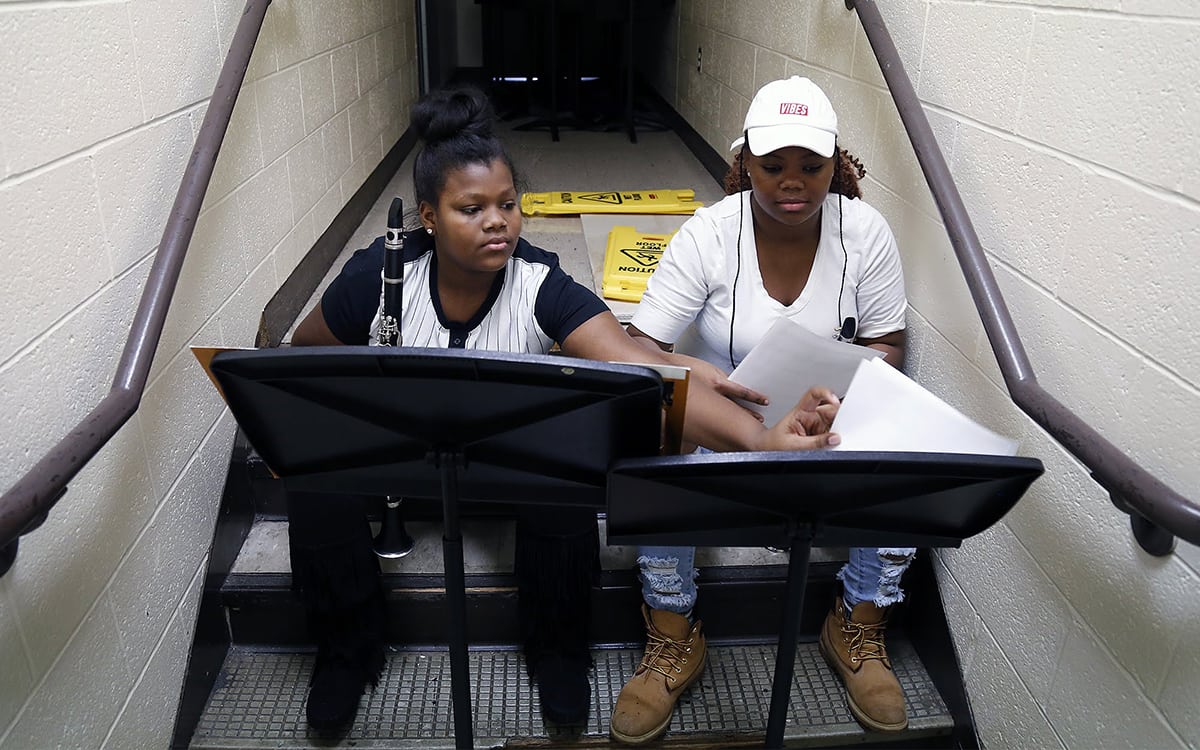

The performing arts at Sto-Rox are limited to band and chorus. There is no orchestra. No drama club.

Students in band class get new reeds or drum sticks whenever teacher Suellen Engelhard is able to raise enough money through donor websites. She frequently posts on the DonorsChoose.org website for band equipment, instrument repairs and lunches for band camp.

“Never when I went to music school did I think I would need to do this,” she said.

The band needs $30,000 to replace the 30-year-old band uniforms the students are wearing. Students requested capes on their uniforms when they saw them at a band festival, but Engelhard had to tell them the capes are too expensive.

She was told if she can raise half the $30,000, the district will pay the rest. She’s inching toward that mark. A January spaghetti dinner sponsored by an alumnus raised about $2,700. Mancini’s Bakery donated $2,000. Special education teacher Joe Grushecky and his band the Houserockers held a private benefit concert that raised $3,300 and Grushecky fans donated an additional $1,250.

The district recently ordered the new band uniforms.

The Band (clockwise): In December 2017, students Alayha Lee Rice (left) and Asia Johnson practice playing clarinet in a hallway at Sto-Rox Junior-Senior High School. Band uniforms that are about 30 years old hang in storage. In August, members of the school marching band practice on the football field. Instruments that need repairs are kept in a storage room, as seen in December 2017.

(Photos by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)Engelhard’s children attend the Canon-McMillan School District in Washington County where she sees students with high-quality musical instruments and private lessons. She wishes Sto-Rox students had the same.

“It makes me sad for them. I think if you were born 2 miles away you would have a big fireplace in your library,” she said, referring to the fireplace in the new $50 million Montour Elementary.

“When students travel to other schools, they are amazed at what they see,” Engelhard said. When they went to Moon Area High School for a band festival, they wondered aloud, “This is a school?”

Wearing multiple hats

On a December morning, Principal Beck dispensed medication to a student with diabetes. Having just a half-day nurse means Beck stores medication for several students. “It doesn’t even phase me anymore,” Beck said of performing nurse duties.

He’s not the only one to wear multiple hats. Teachers take turns monitoring the in-school suspension room, overseeing Keystone Exam tutoring sessions or teaching multiple academic subjects to allow students to have the modest variety of electives that are available in the schedule.

The teachers also volunteer, without compensation, to supervise clubs and sports. An after-school robotics team and a football team for seventh and eighth graders exist because of teacher volunteers as does a wrestling program that doesn’t have enough students for a team but allows individual wrestlers to compete in tournaments.

AP Chemistry is available because a science teacher offered to create and teach it for no extra pay, said guidance counselor Joe Herzing. “A math teacher had five different courses to prep for but, in order to keep our offerings to where they are, we need to do that,” Herzing said.

Students play basketball in the Sto-Rox Junior-Senior High School gym in December 2017.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)Students still feel cheated.

“It’s the same teachers teaching different things,” said Cassidy Baradah, a cheerleader who is starting her senior year.

Some honors classes are combined with regular classes. Such was the case with Lexi’s honors trigonometry class taught by Sue Kattan. Animated and enthusiastic, Kattan tried her hardest to capture the attention of students through the difficult exercises she was walking them through on a whiteboard.

Some students stuck with her. Others had their heads on their desks.

“Some of you want to quit on me but I’m not going to quit on you. I know you can do it,” Kattan said.

Up the hill

A frequent reference among students and staff at Sto-Rox is how things are “up the hill” in Montour.

Feb. 22 was the kind of day that water would once again seep through the roof of Sto-Rox Junior-Senior High School as rain poured from the sky. But “up the hill” at the new Montour Elementary, there was a celebration for the grand opening of its Brick Makerspace, a room filled with Legos and other building materials and equipment.

The large area was included in the design of the new school, and Montour officials said it was the first space of its kind in the world. The opening was attended by officials including Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald and the head of LEGO Education North America.

Students build with Legos inside the Brick Makerspace, a room filled with Legos and other building materials and equipment at Montour Elementary on Feb. 22, 2018.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)Montour Elementary also houses a Minecraft Education Lab, where teachers craft lessons using interactive Minecraft software.

At the time, neither Sto-Rox Junior-Senior High School nor its schools for grades K-3 and 4-6 had makerspaces. But with a $16,500 Catalyst grant from the Allegheny Intermediate Unit, makerspaces are being created.

Even the brightest Sto-Rox students worry about what they will be lacking when they arrive at college. Will they be overwhelmed by the choices provided in higher education that they were previously not exposed to? Will they have the tech competency to keep up with online classes? Their teachers at Sto-Rox wonder as well.

In a comparative religions class in March, students watched a CNN student video, then read an article about Iran’s compulsory hijab law. They penciled their thoughts on the back of the printed article.

It doesn’t phase students to be handed paper and pencil. They are used to it.

“These kids are going to go to college and they’ve never printed their own work.”

“We’re mostly a paper school, not electronic,” Lexi said.

Teacher Kyle Acre had an interactive whiteboard but not all of the technology to make it fully functional. There were some new boards on wheels teachers can sign out for classes, but there had been no training on them yet so he doesn’t use them.

Acre noted that students can’t print anything either because there are too few printers for every student to have access. They are restricted for teacher use only.

“If students need to have something printed, they must put it on a flash drive or email it to a teacher to have it printed. Most don’t have printers at home. These kids are going to go to college and they’ve never printed their own work,” Acre said.

Science teacher Anthony Martini requires students in his honors inquiry and scientific method class to use Chromebooks for their work. One lesson involved creating an Excel spreadsheet.

Some of his students told PublicSource they prefer paper and pencil because their typing skills are poor. “I’m not good with keyboards,” said Ryan Lipovsek, who will be a senior.

It’s not just the students who get shortchanged. Sto-Rox teachers earn less than their counterparts up the hill.

The 2017-18 starting salary for a teacher with a bachelor’s degree in Sto-Rox was $40,900 as compared with Montour at $45,875. That same year, Sto-Rox teachers with a bachelor’s degree at the top of its 18-step scale made $81,930, while teachers with a bachelor’s at the top of Montour’s 17-step scale earned $105,308.

Special Education

Close to 19 percent of Sto-Rox students are designated as special education, as compared with 13 percent at Montour.

The state provides a flat 16 percent funding for special education (based on an assumption that special education services will be needed by that percentage of the student population). If a district is like Sto-Rox and has more than 16 percent of its students needing special education, the school district absorbs those costs, which further exacerbates financial woes.

Herzing, the guidance counselor, and Superintendent Dalmas said they believe the traumas of living in poverty contribute to emotional and mental health disabilities of students.

Herzing counts the stresses off on his fingers: “Housing instability, moving from place to place with their families. Some are working as much as 30 hours a week outside of school. Being kicked out at age 18, told they are on their own.”

Drey Frenzley has grown up in Stowe Township, just a few minutes’ walk from Sto-Rox Junior-Senior High School. The 17-year-old says he likes the close-knit community where he lives, but he describes it as “rough-ish” — not the safest place but still not as bad as the world perceives it. Drey is about to start his senior year at Sto-Rox and plays defensive tackle on the school’s football team.

(Video by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)Drugs and street violence seem to bring more than the usual number of deaths to the students’ families, Herzing added.

On July 28, Jassim Al-Maleky, a 2018 Sto-Rox graduate, was fatally shot in Kennedy while watching a fistfight with a group of people.

To help deal with those stresses, the junior-senior high school has an emotional support classroom and on-site counselors from Pressley Ridge, a nonprofit that educates children with special needs.

“There are so many kids that need it, it’s cheaper to bring them on-site than to send the students off-site to schools,” Dalmas said.

Finances

In January, Sto-Rox officials were beginning to think about the 2018-19 budget and whether they would be able to continue to maintain jobs and programs for the next year.

Then, that same month, state Auditor General Eugene DePasquale released an audit report stating the Sto-Rox and Aliquippa school districts are among the state’s most struggling districts with costs, such as pensions and health care, that are exorbitant and out of their control. Aliquippa was already on the state financial watch list, and DePasquale predicted Sto-Rox may soon follow.

Among violations cited in the audit is that Sto-Rox did not make required pension payments. But DePasquale was not overly critical. The reason: The money was needed to make payroll.

“These school districts almost have no way to get through the year without, in a sense, trying to duct tape it together,” DePasquale said in a recent interview.

Dalmas and the board were able to balance the 2018-19 budget and reduce the district’s $3.9 million deficit by about $400,000.

Even before the struggle of the recent budget, Dalmas last fall lamented on how much the district has cut from its programs.

“We’ve cut as deep as we can cut. There is nothing else we can cut,” Dalmas said. “We offer honors classes and they are small, maybe eight to 11 kids. I walk by and I think, ‘Should I be paying a teacher to teach that small [of] a group?’ But these are the kids who have a chance to get out of here.”

Mary Niederberger covers education for PublicSource. She can be reached at 412-515-0064 or mary@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by Jeffrey Benzing.

This project has been made possible with the generous support of The Grable Foundation and the Education Writers Association.