Part of the PublicSource series

Failing the Future

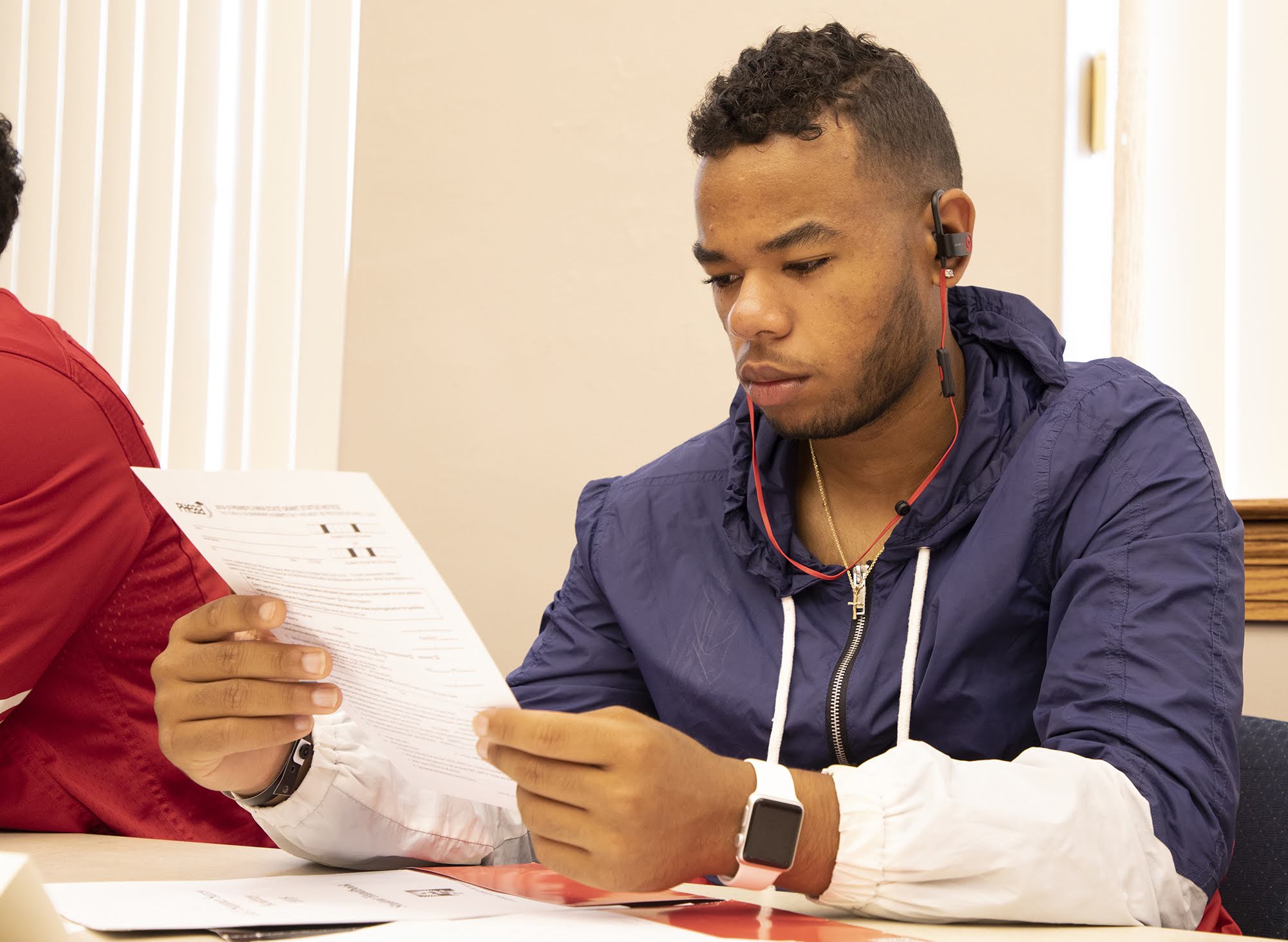

Brycen Simpson didn’t feel prepared for college.

It was less than a week before starting classes at California University of Pennsylvania in August and, as he sat alongside his twin brother, Braden, the 20-year-olds agreed they weren’t ready.

There was so much they didn’t learn in high school, both academically and socially. They felt left behind.

“I know I’m not ready,” said Brycen, who hopes to go into sports management. “I literally think my [high] school really didn’t push the students hard enough.”

The twins, who graduated in May from Valley High School in the New Kensington-Arnold School District, participated in Cal U’s pilot Summer Success Academy in hopes of learning what’s ahead for them this fall.

New Kensington-Arnold is a small district in the northwest corner of Westmoreland County with 1,971 students — 58 percent of whom are economically disadvantaged. State funding made up about 58 percent of the district’s revenue in 2017-18, while about 31 percent was set to come from local tax revenue, according to its budget.

Braden, a criminal justice major who wants to be a state trooper or SWAT team member, said that in high school he was told he was “wasn’t mentally prepared” for classes he wanted to take, like calculus or trigonometry. He might need to take them in college. He knows he needs the academic support. “Sometimes I get carried away and lose focus,” he said.

Brycen (left) and Braden Simpson, both 20 of New Kensington, are twins attending California University of Pennsylvania. They started attending the school this semester. Neither felt like their high school prepared them for college.

(Photo by Kat Procyk/PublicSource)The summer program really helped, Braden said.

“It gave me a boost. It let some stress off of my shoulders,” he said. He learned to take better notes in the program and felt the improvement during his first few weeks of college.

Across Pennsylvania, state and local funding play a major role in the classes and extracurricular activities that school districts offer. Wealthier districts tend to rely more heavily on local property taxes because residents can afford to pay more and that is seen in their child’s education. Poorer districts, with lower socioeconomic families, tend to rely heavier on state revenue and often struggle to provide even the basics.

Braden said he noticed other school districts offered things his didn’t. He feels he would have been more prepared for college if his high school had offered more.

Many students are aware of what they do not have and they’re worried about how that lack of access has set them up for a future in higher education or the workforce.

Though some higher ed leaders emphasize there is not always a direct correlation between high school and a student’s academic success in college, several colleges and universities in Southwestern Pennsylvania have options for students who are behind or didn’t have as many opportunities in high school.

Braden said he noticed other school districts offered things his didn’t. He feels he would have been more prepared for college if his high school had offered more.

Options range from pre-college course work to summer sessions and lower-level classes to catch students up.

There doesn’t appear to be a uniform approach to helping students whose secondary education may have been inadequate. In the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education, which includes Cal U, the 14 universities each have their own offerings.

Not every college in the state has extra programs for students in need, aside from extra tutoring. Chatham University and the University of Pittsburgh said they don’t offer this type of programming, but indicated that students are supported individually in a variety of ways.

Students aren’t destined to fail if colleges and universities don’t offer any academic prep, though some higher ed leaders pointed out that social and emotional support are just as, if not more, important when it comes to succeeding in college. Just knowing that students have the drive and skills can be enough; they can teach the academics.

Giving them a chance

Ahnesti Wicks switched high schools four times.

Each time, she found herself with a new set of classes lined up for her. It seems to her that many things — things she needs as she starts as a freshman at Cal U this fall — slipped through the cracks as she moved from high schools in rural Pennsylvania to Pittsburgh Public Schools and McKeesport, where she graduated.

The 18-year-old dreams of becoming a veterinarian, so she doesn’t want to start college from behind.

Wicks enrolled in the five-day Summer Success Academy at Cal U. There, she made sure her financial aid was set up and learned basic studying skills.

“I feel like this is me preparing myself. Like with this program, because I’m here, I’m preparing myself,” said Wicks, who now lives on her own in Clairton.

Ahnesti Wicks, 18, of Clairton, is currently listed as a pre-vet major, at California University of Pennsylvania. However, she’s still exploring different biology programs offered at the university to ultimately become a vet. She has not decided if she wants to specialize in either small or large animals.

(Photo by Kat Procyk/PublicSource)The Summer Success Academy included 32 students from a five-county region, many of whom came from low socioeconomic status areas, said Karen Amrhein, director of academic success initiatives. Some chose to take the program themselves while others were recommended for the program.

The free program prepares them with a range of tips, from time management skills to reminding students to put their cell phones away in class.

The students are also paired with a graduate assistant who will “keep them on track” and review study skills with them, Amrhein said.

Students who are coming from behind, whether they have a lower GPA in high school or are identified by admissions staff as needing extra support, are also enrolled in the Support for Success program at Cal U, said Lisa Glasser, a student success specialist.

“This is really providing them with the academic tools that they will need to succeed here on campus.”

Students in this program are also paired with a graduate assistant. On alternating weeks, students attend workshops on study tips, communication skills, test anxiety or any area where they may need extra support.

“This is really providing them with the academic tools that they will need to succeed here on campus,” Glasser said.

Knowing that “all school districts were not created equal,” the university uses information like where a student attended high school and their GPA to recommend them for the Support for Success program, said Daniel Engstrom, associate provost and associate vice president of academic success.

The high school a student attended is not taken into account for admission to the university, Engstrom added.

The school also requires every freshman to take a first-year seminar that is an orientation to the university. In the first-year seminar, students are put into “learning communities” where they take the same classes as other first-year students to create a bond, Engstrom said. “We are very, very intentional about all the things we’re doing so we build relationships between students.”

Starting with the basics

For students who aren’t ready for college math, English or reading courses, the Community College of Allegheny County [CCAC] offers remediation, or pre-college courses. While they don’t count toward a degree, the classes are covered with financial aid credits.

Remediation “is not a free pass into moving toward college. It is an additional barrier,” said Stuart Blacklaw, CCAC provost and executive vice president. When students start from behind and need to take courses that don’t offer credits toward their degree, that means even more time and money they need to spend on college to get to the finish line, he added.

For students who are struggling in one area of math, CCAC also uses a computer software program that helps zero in on the areas students are struggling with and teach them specific lessons, like how to multiply fractions, for example.

The school also offers a student success course that teaches the basic study skills students will need, Blacklaw said.

Each year, between 1,200 and 1,400 students enroll in remedial English and reading courses. Between 2,500 and 3,000 students take remedial math, Blacklaw said. The courses are offered at all CCAC campuses. In 2017-18, 26,243 students were enrolled in for-credit courses at CCAC.

Between 55 and 60 percent of the students who take a remedial course take more than one. Students enrolled in more than one remedial course are assigned a success coach, which Blacklaw compares to an athletic coach who encourages you to do more with that “drop and give me 20” style of motivation.

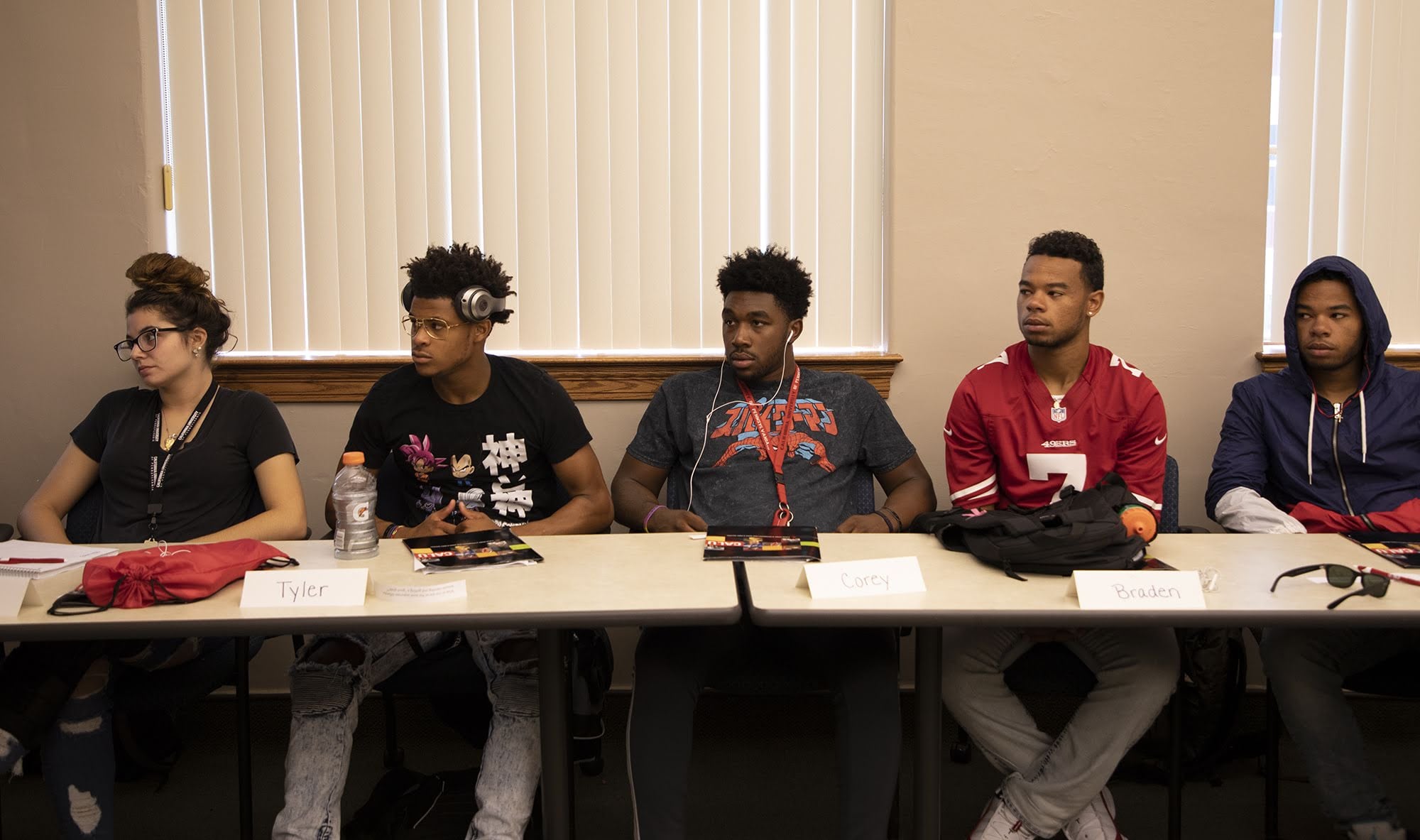

From left to right: Erica Thorniley, Tyler Walker, Corey Thomas, Braden Simpson and Brycen Simpson watch a presentation at California University of Pennsylvania during the Summer Success Academy. The pilot program is meant to help upcoming freshman who seek extra college preparation prior to classes beginning in the fall semester.

(Photo by Kat Procyk/PublicSource)The school does not track which high schools the students who take remedial courses come from, Blacklaw said. At CCAC, they have found that high school performance alone is not a deciding factor in success.

“It has almost nothing to do with the kids and which school they went to. It has everything to do with what the kid’s life is like,” Blacklaw said. “So a kid without the wraparound support in their lives, regardless of what school it is that they attend, are going to find additional challenges. And if the school can’t fill in that gap for any of those challenges, of course, that makes it worse.”

CCAC brings in community agencies to relieve burdens from these students and even added a food pantry on its campuses in recent years.

Many students who attend CCAC are working full-time jobs or taking care of their families.

“These are all distractions and, quite often,” Blacklaw said, “you’re going to choose your child over your class. You’re going to choose your paycheck over your class.”

Scholarships, partnerships and working together

Lorin Ballog likes to stay busy. She volunteers at her church. As a student at West Mifflin Area High School, where the 18-year-old graduated in May, she participated in a long list of clubs and activities, from marching band to a group fighting the stigma of mental illness.

Coming from a single-parent family, she worried about paying for college. She didn’t know all of the clubs and volunteer work she did could pay off financially.

Pennsylvania State University is trying to make college accessible and affordable for all students, said Jacqueline Edmondson, chancellor and chief academic officer at the Greater Allegheny campus in McKeesport. As part of the initiative, the school began offering RaiseMe microscholarships at the Greater Allegheny campus about two years ago. The RaiseMe program, which has more than 250 college partners, is geared toward expanding access to higher education, specifically among low-income and first-generation students.

Even for students in “under-resourced schools,” there’s still a lot they can be doing outside of the classroom to prepare themselves for college, Edmondson said.

Lorin Ballog, 18, of West Mifflin, poses for a portrait in her dorm room at Penn State Greater Allegheny.

(Photo by Kat Procyk/PublicSource)Penn State Greater Allegheny partnered with eight school districts for the program, where students earn points toward scholarships for things like volunteering at a nursing home or participating with a mentoring organization. Partner high schools include McKeesport Area, West Mifflin Area, South Allegheny and Steel Valley, along with Perry, Brashear, Taylor Allderdice and Carrick high schools in the Pittsburgh district.

“It does help them to think sort of holistically about the kinds of things they could be doing as they’re getting ready for college,” Edmondson said.

Ballog received about $4,000 from the RaiseMe microscholarships, or $1,000 for each year of college.

On Penn State’s Greater Allegheny campus, almost half of the students are the first in their families to attend college. Nearly half of the students at the school are PELL grant eligible — meaning they meet certain financial aid requirements and are coming from “economically depressed areas,” Edmondson said.

Edmondson said she knows there are a lot of students who are “highly talented, but because they’re coming from under-resourced high schools may not have had all the opportunities that their more privileged peers would.”

On a recent staff retreat, faculty talked about what they’re looking for in students: problem-solvers, students who are hardworking and resilient.

“It does help them to think sort of holistically about the kinds of things they could be doing as they’re getting ready for college.”

“Those are the qualities of the students that we feel would be really successful here because we know we can help them with the academic side of the aisle,” she said.

The university also offers a Pathway to Success: Summer Start Program [PaSSS], where students can take six credits to get a jumpstart on college. The Greater Allegheny campus started offering the program this summer.

Ballog, who participated in the PaSSS program, said she learned so much about college from the summer courses and staying on campus that she feels like a second-year student.

Carnegie Mellon University also offers introductions to campus and different disciplines. A CMU program provides opportunities for rising juniors and seniors coming from underrepresented minorities, low socioeconomic backgrounds and inner-city schools to learn creativity and problem-solving while on the Oakland campus. The Summer Opportunities for Access and Inclusion program does not charge for tuition, housing or dining.

One track, the Summer Academy for Math and Science, takes students underrepresented in the STEM field and aims to give them a jumpstart, particularly for those looking to attend a college like CMU, said Abby Simmons, associate director of media relations.

The school also offers a pre-college artificial intelligence course and pre-college fine arts programs in architecture, art, design, drama and music.

Being a part of campus is just as important

Paul-James Cukanna, vice president for enrollment management at Duquesne University, emphasized that a person’s economic background does not always correlate to their academic success in college.

The university does not offer a pre-college track like CCAC, but it does have programs for students who are behind in academics and those tailored to help students get adjusted to university life.

Most programs at the university enroll students with a B average from high school, Cukanna said. The school also offers a “test optional” admission, where students are not required to submit SAT or ACT scores to count toward general enrollment.

This comes from the understanding that everyone may not be good at taking tests, said J.D. Douglas, director of retention and academic achievement.

The university also offers a summer bridge program through its Spiritan Division, where students can take six credits before starting their fall semester. Each has a built-in study class and zero-credit seminars to help them get adjusted.

This type of program is great for students who may struggle in courses like philosophy, which a lot of high schools don’t offer, Douglas said.

The goal at Duquesne is to enroll students from all walks of life, Cukanna said.

When it comes to programs for students, Duquesne takes a “broadcast view rather than narrowcasting on certain populations of students, because we know all students benefit from it,” Cukanna said. “There are kids from Blue Ribbon schools struggling as much as kids maybe located in a lower socioeconomic background and community. It doesn’t make any difference what high school because we’re looking at the student.”

Stephanie Hacke is a freelance journalist in Pittsburgh. She can be reached at stephanie.hacke@gmail.com or on Twitter at @StephOnRecord.

This story was fact-checked by Tyler Losier.

This project has been made possible with the generous support of The Grable Foundation and the Education Writers Association.