Part of the PublicSource series

Failing the Future

It was 1985. Jerry Longo was on his way to his new job as superintendent of the Steel Valley School District. He gazed at the plumes of smoke rising from the USX Homestead Works as he drove over the former Homestead High Level Bridge.

That billowing smoke meant the mill was still operating at a time when others had been shuttered, and a working mill meant real estate tax revenue for the school district.

But that changed a year later when the remaining portions of the once massive plant closed for good. No more billowing smoke. No more mill tax revenue for the district.

Steel Valley went from “having pretty much everything they wanted to ‘Can we keep the lights on?’” said Longo, now on the faculty of the University of Pittsburgh School of Education.

Longo used the story to demonstrate how closely a school district’s health is tied to the wealth of its communities.

The issue is at the center of a Commonwealth Court case that argues the state underfunds schools and that its method of distributing education funds is flawed because its reliance on local revenue fails to ensure that all school districts have the resources necessary to provide an adequate education to students.

Officials from the Education Law Center and the Public Interest Law Center, who represent plaintiffs in the lawsuit, say Pennsylvania provides about 38 percent of school districts’ funding — ranking it 46th of the 50 states.

Districts with strong local tax bases can make up for the lack of state funds and are able to offer students state-of-the-art technology, rich art and music programs, an array of Advanced Placement courses and a large selection of extracurricular and sports opportunities.

But districts that lack the ability to raise significant local revenue through taxes are operating with bare-bones curriculum, limited technology, extracurricular and sports options and deteriorating facilities. They’re also often going without librarians, school resource officers and full-time nurses in their buildings.

Crumbling steps can be seen on the visitors bleachers at Aliquippa Junior-Senior High School's football field. The section has been permanently closed.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)The declining conditions in the schools prompt more families to move their children to charter schools. Paying charter school tuition drains struggling districts funds even further, often prompting more cuts.

In most cases locally, the districts that have the least local wealth are often among those with the highest minority enrollments, which means that funding inequities hit students of color the hardest.

School segregation is a direct result of housing segregation, said Cheryl Kleiman, staff attorney with the Education Law Center. “Students of color are more likely to attend schools with less state funding and live in communities that can’t make up that gap,” Kleiman said.

And the gaps are large.

“When we look at that disparity between affluent and poor districts, we’re in the bottom quartile,” said Pennsylvania Department of Education Secretary Pedro Rivera in an interview with PublicSource.

“So we know that there are more affluent communities funding education at a much higher level, sometimes anywhere between $22,000 per child in an affluent school district and just over $10,000 per child in some of our poorer school districts,” Rivera said.

Pennsylvania Secretary of Education Pedro A. Rivera speaks with the executive director of Intermediate Unit I, Charles F. Mahoney III, at its headquarters in Coal Center, Pa., on June 12, 2018.

(Photo by Kat Procyk/PublicSource)A new state education funding formula that gives weight to the number of students living in poverty, the number enrolled in charter schools and districts’ ability to generate local wealth was enacted in July 2016. But it has done little to close the funding gap between districts because it applies only to new money appropriated by the state.

In the 2018-19 budget, $538 million of the $6 billion allocated for education in Pennsylvania will be distributed according to the new formula.

“They are placed in a position where they are not even prioritizing, ‘Do I teach German or Spanish or French?’ It’s, ’What do I do to keep the doors open and keep the kids relatively safe?’”

Gov. Tom Wolf recently announced that he would like to see all school funding distributed through the formula, but such a change would require legislative action. He later clarified that statement, saying he supports the change after more funding is applied to education. Rivera told PublicSource more state funding is needed so that no districts lose funding under the new plan.

In the meantime, the current school funding system forces less wealthy districts to make tough decisions that can compromise educational standards, said Linda Hippert, the recently retired director of the Allegheny Intermediate Unit.

“They are placed in a position where they are not even prioritizing, ‘Do I teach German or Spanish or French?’ It’s, ’What do I do to keep the doors open and keep the kids relatively safe?’ while neighboring districts because of their tax base can offer the sun and moon and stars,” said Hippert, former superintendent of the South Fayette School District.

Local tax revenue is raised largely through real estate millage, with a mill of taxes equal to $1 per each $1,000 in real estate assessment. Because the total assessed value of real estate varies from district to district, the amount of money a mill can generate also varies widely.

A PublicSource analysis that includes both in-district and charter school enrollment shows that in Allegheny County, the amount of real estate revenue generated per mill of taxes ranges from $942 per student in Quaker Valley to $117 per student in the Duquesne City School District. Pittsburgh Public Schools generates about $18.2 million per mill, which is about $689 per student.

A look at revenue in districts of similar size adds more nuance to the depth of this disparity.

Take for instance the McKeesport Area School District with about 3,390 students in district schools, according to its state School Performance Profile [SPP] (the Department of Education’s annual assessment on schools throughout the state). There, a mill of taxes generates roughly $780,000.

Revenue from 1 mill at two school districts of similar size

Compare that with the Gateway School District, which has an enrollment of about 3,333 students in district schools and where a mill of taxes is worth about $2.3 million.

District enrollment determines the level at which students compete in athletics, music and other extracurricular activities.

The districts don’t have the same ability to generate revenue, said David Seropian, a former McKeesport Area School District business manager who now serves as a financial consultant for the district. “When we have 19 mills here and [Gateway] ha[s] 19 mills there, they bring in around three times what we bring in.”

McKeesport’s financial situation becomes even more dire when charter school students are included in its budget. McKeesport paid tuition for 514 students to attend charter schools, according to its SPP. Gateway had 183 students in charter schools.

For the 2018-19 school year, McKeesport raised taxes 2.11 mills. The increase will provide about $1.6 million.

“Something has to change with the way schools are funded because there are only so many things we can do,” Seropian said.

For this school year, McKeesport Area cut its two remaining librarians who had split their time among the district’s schools. Seropian said he thought the cuts would have minimal effect on students’ educational experiences because classroom teachers could still have their students use the library.

Rivera, however, spoke highly of librarians’ impact on education: “Librarians across the commonwealth are doing so much more than traditional library science. They’re building makerspaces because it’s in their libraries. They’re building computer science applications space. They’re integrating technology.”

Longo, after seven years in Steel Valley, became superintendent in Quaker Valley, a district with a healthy residential and commercial tax base.

“In Quaker Valley, we weren’t thinking about keeping the lights or the heat on. Our teachers were fairly well compensated. We had the curriculum and athletic program that you would find at bigger schools in a little high school of 700 kids,” Longo said.

Haves and have-nots

The differences in what local wealth can provide are evident in Twitter feeds alone.

Some districts boast of percussion ensembles, dance teams, elementary strings programs, Odyssey of the Mind competitors, Latin leagues and, in North Allegheny, a coffeehouse classroom.

North Allegheny would not allow PublicSource to visit the classroom for the purposes of this story. “My concern is that there would be a perception that NA would look ‘good’ or ‘better’ by being compared directly to other districts that may not have the same resources as us,” district spokeswoman Emily Schaffer wrote in an email.

In Beaver County’s Aliquippa School District, there is no foreign language teacher or Advanced Placement courses. In Sto-Rox, students read literature that is printed from free online sources because they can’t afford books. In Clairton, there is no elementary art teacher.

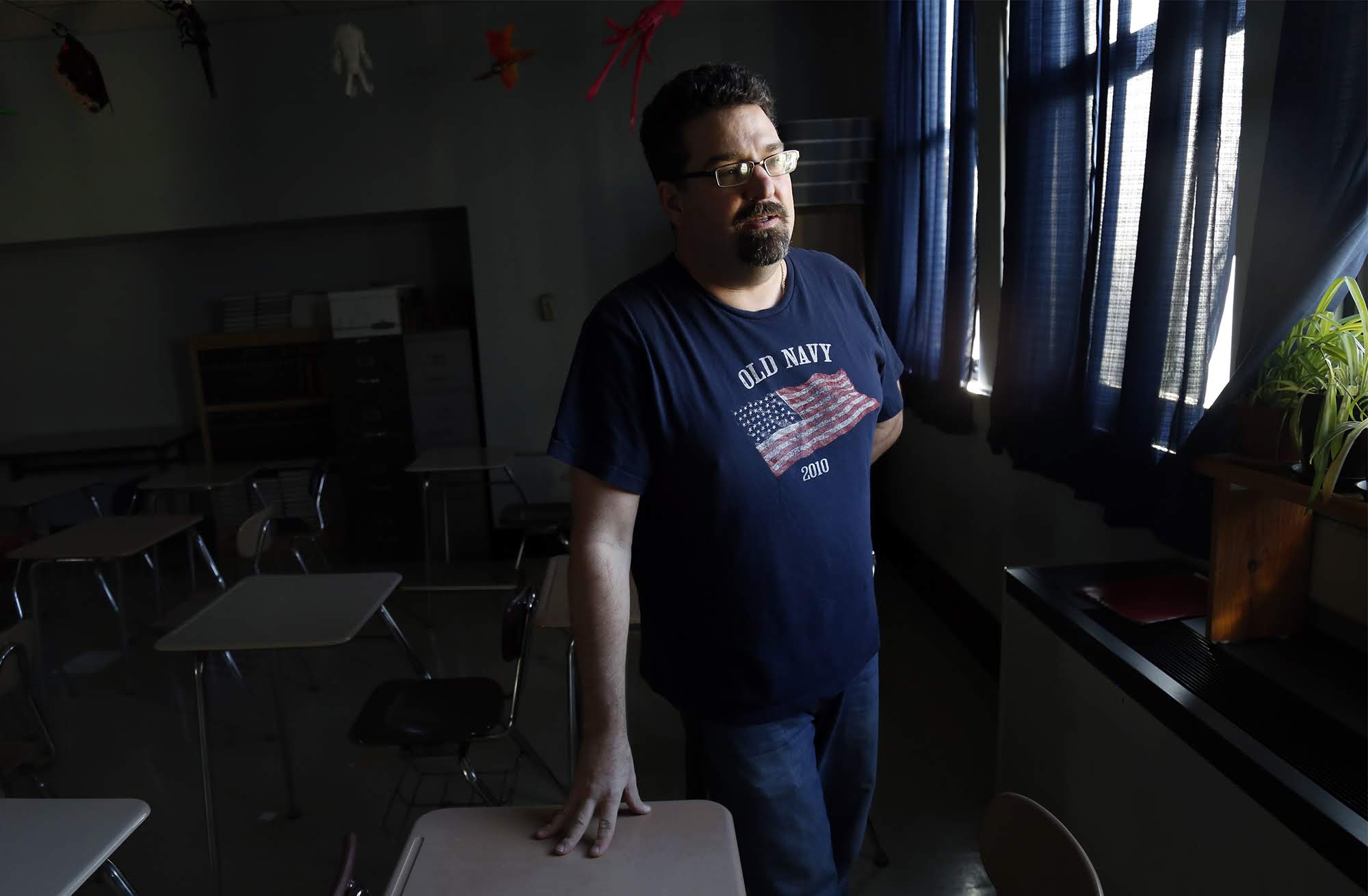

“The ‘haves’ continue to get more. ‘Have-nots’ get nothing. How far down the list is a coffeehouse classroom in terms of what you need to run a school?” said Kenneth Lex, a Sto-Rox language arts teacher who raises money from donor sites, like DonorsChoose.org, for classroom materials.

Ken Lex, language arts teacher at Sto-Rox Junior-Senior High School.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)Here is how inequitable funding in Pennsylvania affects just about every aspect of a student’s experience:

Academic Scores

Among the 42 suburban middle and high schools in Allegheny County, Sto-Rox and Clairton rank among the bottom three with SPP scores of 41.5 and 47.6, respectively. The highest possible score is 107.

The Clairton district brings in the second lowest amount per mill, $118 per student, and Sto-Rox has the sixth-lowest rate at $178.

Upper St. Clair High School had the highest SPP score at 100.2, followed by Fox Chapel Area High School at 99.1. When it comes to local millage revenue, a mill in Upper St. Clair brings in $512 per student and Fox Chapel yields $836 per student.

In addition, a RAND Corporation study from 2015 found that in Pennsylvania, “the achievement gaps between students classified by race-ethnicity, economic status and parent education are among the largest in the country.”

Course offerings, textbooks

The difference in course offerings among districts is staggering.

According to SPPs from fall 2017, the Fox Chapel Area School District offered the most Advanced Placement courses of any high school in the county at 31. Cornell had the fewest AP courses, with one. Some of that difference can be explained by enrollment — Fox Chapel with roughly 4,100 students compared with 630 at Cornell.

But again, looking at districts of similar size, Gateway offered 18 AP courses, while McKeesport had nine.

In districts like Sto-Rox and Aliquippa, which is one of four districts on the state’s financial watch list, the limited number of electives is made possible because some teachers take on multiple courses.

As with other struggling districts, Aliquippa’s financial downfall can be traced to the town’s loss of a steel mill. The former Jones & Laughlin Steel-Aliquippa Works once stretched for 7 miles along the Ohio River. But when it closed in the mid-1980s, 8,000 people lost their jobs. No other industry has filled that void.

At Aliquippa High School, where no AP courses are offered, students said they can choose from about 10 electives. But having the same teacher over and over again gets tedious, the students said.

AP course offerings between school districts of similar size

“They sound good but when you get in there you are bored,” said Larry Walker, who is starting his senior year.

Aliquippa Junior-Senior High School, which houses grades 7-12, has the lowest SPP score among middle and high schools in Beaver County at 42.9. It also has the highest enrollment of black students (76 percent); and nearly 100 percent of its students are considered to be economically disadvantaged, the highest rate among the county’s schools.

One art teacher serves grades 7-12. “We’ve had the same teacher since seventh grade,” Larry said. “The older you get, the more you are supposed to open your mind. But you go to class and you are seeing all of the same faces I’ve seen since I was 11 years old.”

Larry said some textbooks are so out of date that teachers don’t use them. The only foreign language — Spanish — is offered online.

“Our kids are often put into elective classes that they don’t really want because that is what’s available,” said Ellen Hermes, Aliquippa Junior-Senior High School guidance counselor.

“When my kids went to Quaker Valley, they could take classes that ranged from the Civil War to creative writing. Whereas here we do a really good job with the basic courses. It’s the extras we can’t offer because we just don’t have the staffing.”

Facilities

In the past decade, the Mt. Lebanon School District built a new high school at a cost of $110 million, Bethel Park took on a $91 million renovation and Montour underwent a $50 million upgrade of its high school and construction of an elementary school at the same price.

West Jefferson Hills School District is completing construction on a new $95 million high school, and, in June, the Peters Township School District approved contracts for $83 million in work on a new high school.

In Aliquippa, Larry plays football and runs track in a football stadium built in 1937. The field is in such poor shape that the visitors bleachers have been permanently closed, the grass field is rocky and rutted and the fieldhouse locker room is dark, dirty and in disrepair.

Football teammate Solvauhn Moreland, 18, said he is embarrassed when college recruiters come to watch games and practices and hold meetings in the dingy fieldhouse.

“They walk in the locker room and just look around,” Solvauhn said. “Sometimes there is no water or heat. It’s raw.”

Aliquippa team members point to North Allegheny, where the stadium has turf that was replaced in 2016, the same year a $500,000 scoreboard with instant-replay capacity was installed. The scoreboard was paid for through a private fundraising effort.

Aliquippa Superintendent Peter Carbone is photographed in the visitors bleachers at Aliquippa Junior-Senior High School's football field. The field is in such poor shape that the visitors bleachers have been permanently closed, the grass field is rocky and rutted and the fieldhouse locker room is dark, dirty and in disrepair.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

A coach's office in the Aliquippa Junior-Senior High School fieldhouse.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

A restroom in the Aliquippa Junior-Senior High School fieldhouse.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

A scoreboard on the Aliquippa Junior-Senior High School football field.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)In nearby Freedom Area School District in Beaver County, about $1.4 million was spent this summer on turf and a new track at the high school stadium.

To practice for track meets, the Aliquippa team runs in the school hallways, where they lay tape to measure distance, or in the school parking lot. Sometimes they are permitted to use the track at Hopewell High School after that school’s team is finished.

“Why is [funding] so unequal?” said Elverna Cuffie, Aliquippa board president. “There is so much stacked against us. You look at North Allegheny and you look at us. What do you do?”

Musicals

High school musicals are commonplace in many districts, and they come with budgets of tens of thousands of dollars. Fox Chapel’s production of “Shrek the Musical,” which included spectacular scenery and costumes, had a price tag of $76,914. Of the total, about $42,000 was covered by the sale of $15 tickets.

But in districts like Sto-Rox, Clairton, Aliquippa and Wilkinsburg, before its high school closed in 2016, there has been no musical for years.

Aliquippa Superintendent Peter Carbone was shocked at the total of the Fox Chapel musical. He’d like to restart the effort to hold musicals at his high school, but said the budget “will be more like $7,600.”

School safety

The ability to hire security staff for schools also varies widely, with wealthier districts beefing up and poorer districts left without.

The North Allegheny board recently approved hiring full-time resource officers for its intermediate and high school campuses starting in the 2018-19 school year at a cost of $225,000 annually.

Gateway recently added 15 armed resource officers.

But districts like Clairton, Sto-Rox and Aliquippa can’t afford resource officers in the schools and rely on relationships with municipal police departments.

Closed secondary programs

Finances already have forced some districts to close their middle and high school programs because they couldn’t afford to continue operating them at a level that served students appropriately.

The Duquesne City School District is in financial recovery and a state-appointed receiver operates the district. (The receiver makes all decisions and the board takes on an advisory role.) The Duquesne district closed its high school in 2007 and its seventh and eighth grade programs several years later. Most Duquesne students attend West Mifflin Area schools, with a small number going to the East Allegheny School District, on a tuition basis.

That arrangement was made possible through state legislation.

“I see that gap getting wider and wider between the haves and the have-nots. …How far behind will we get before we wake up and say we need to do something now?”

The Wilkinsburg school board shuttered its middle and high school programs at the end of the 2015-16 school year and transferred students in grades 7-12 to Pittsburgh Westinghouse Academy 6-12. The Wilkinsburg district must pay tuition to the Pittsburgh district for each of those students. That transfer came through a mutual agreement with the Pittsburgh Public Schools, which now allows Wilkinsburg students to enter lotteries for magnet schools.

The state does appropriate some extra money to struggling schools. This year, Sto-Rox received an extra $500,000 via an Educational Access grant, and Aliquippa received the same amount in Empowerment funding as part of technical assistance provided to districts on the financial watch list.

But, with the exception of Aliquippa using about $100,000 for new curriculum, the districts used the bulk of the money to balance their budgets. Both districts are still operating with deficits — $1 million in Aliquippa and $3.5 million in Sto-Rox.

Private fundraising

In addition to the ability to raise local tax revenue, wealthy school districts also have access to funds raised privately in their communities and through advertising revenue.

Among the districts with foundations dedicated to providing additional money for teachers’ projects and student scholarships are Mt. Lebanon, North Allegheny and Pine-Richland.

According to its website, the North Allegheny Foundation has provided $300,000 in grants for school projects and “thousands more” in scholarships for students since 1989. The website of the Pine-Richland Opportunities Fund reported giving $43,250 in scholarships to students this year and $48,855 for innovative teacher projects.

Those private funds further widen the gap between the wealthy and poor districts.

“I see that gap getting wider and wider between the haves and the have-nots,” Hippert said. “…How far behind will we get before we wake up and say we need to do something now?”

Mary Niederberger covers education for PublicSource. She can be reached at 412-515-0064 or mary@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by Natasha Vicens.

This project has been made possible with the generous support of the Grable Foundation and the Education Writers Association.