Part of the PublicSource series

Failing the Future

More than 1,000 people from across the country gathered in downtown Pittsburgh this week for a national conference focused on increasing college enrollment and graduation rates for students from low-income families or underrepresented groups.

As PublicSource continues its focus on education equity in the Pittsburgh area, some of the roughly 100 sessions at the National College Access Network conference provided ideas on how to support students who are coming from financially struggling districts.

National leaders in the field shared success stories of what is working in their cities and shared best practices. Below, we’re highlighting two initiatives speakers presented at the conference — one that has the involvement of the federal government and other institutions and the other that is more accessible, no matter what community it is.

Aligning public housing and opportunities

Inside several of Los Angeles’ public housing complexes, students from low-income families have the opportunity to visit with an on-site education navigator who will help them create an academic plan, complete financial aid documents and help with college applications.

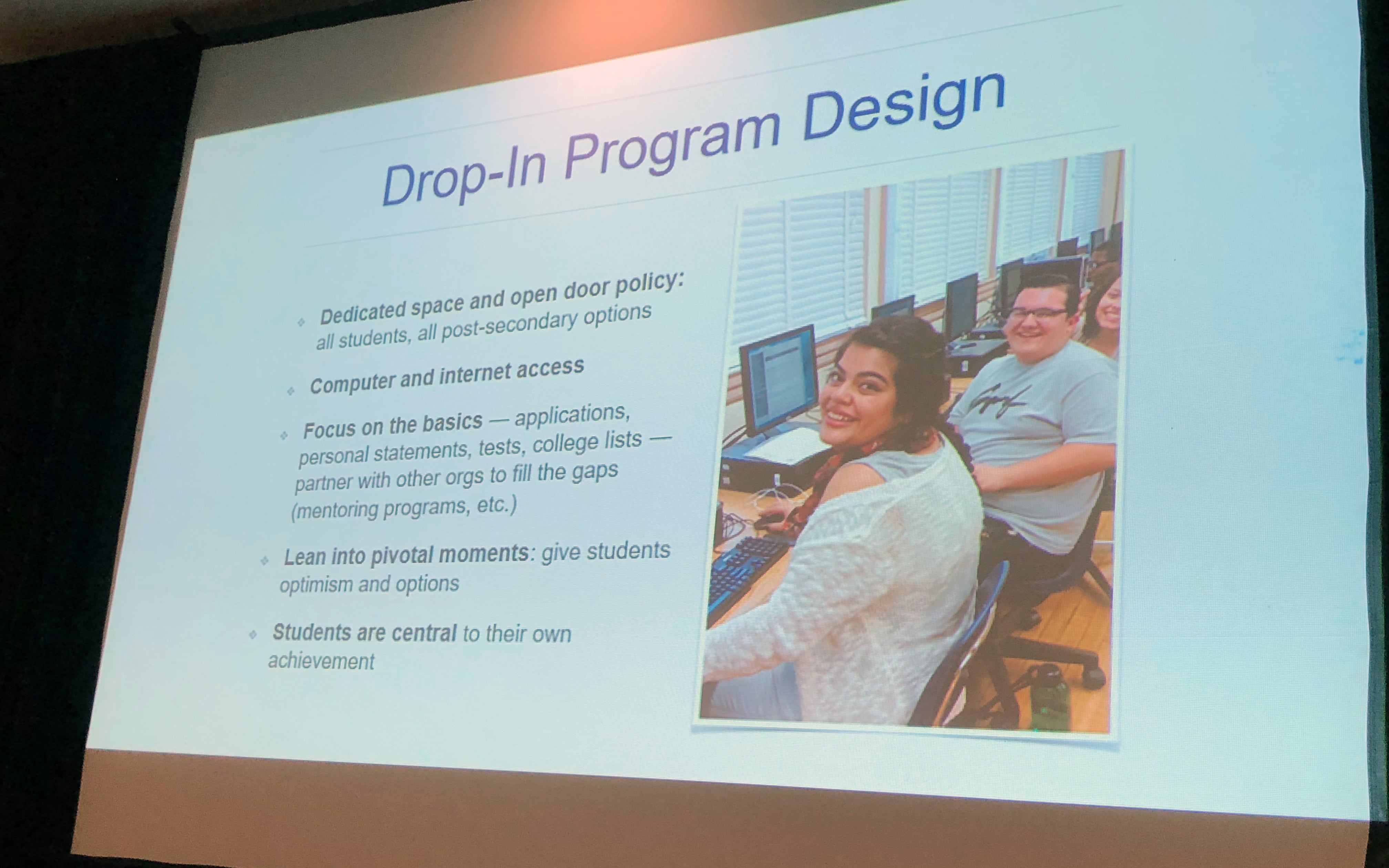

Project SOAR utilizes a “drop-in” model from College Access Plan for its Los Angeles program focused on students ages 15 to 20 in public housing complexes. The presenters included a photo of participating students.

(Photo by Stephanie Hacke/PublicSource)Students can drop in any time from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. The help, and computers, are there for them to make sure they get into and stay in college.

The public housing authority in Los Angeles is one of nine authorities across the country piloting Project SOAR, which is placing education navigators at public housing complexes in a diverse mix of housing authorities across the country. Project SOAR is funded through a 2017 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development [HUD] ROSS for Education grant.

“They’re having one-on-one conversations about individual students needs, goals and plans,” Tess Mullen of HUD told a group of educators as well as nonprofit and public employees on Tuesday.

A year into the pilot program in Los Angeles, Alison De Lucca, executive director of the Southern California College Access Network, talked about the successes of having a person inside the public housing complexes, working directly with students. The programs are open to anyone between 15 and 20 years old who live in a public housing complex.

When the opportunity for federal funding came up, the Los Angeles public housing authority sought the help of De Lucca’s organization to write the grant and has since contracted them to run the on-site program.

De Lucca tapped into resources she already had across the area to build the program, like a connection with Mo Hyman, executive director of the College Access Plan. The College Access Plan is a Pasadena, California-based nonprofit that works to improve knowledge of higher education and matriculation among low-income and first-generation college-bound students in the area’s public schools.

“We had 30 seniors who were all accepted to college with great financial aid packages. That’s a huge success.”

They used College Access Plan’s model in Los Angeles to create drop-in college access help. All they needed was a dedicated space, somewhere kids would know they could go to consistently. They needed computers and Internet access and to focus on the basics: Get them to and through college, Hyman said.

They celebrate every success in the students’ lives and often remind them that it is they, the students, who are creating their own success, Hyman said.

Last school year, the program focused on getting high school seniors into college and finding them financial aid opportunities.

“We had 30 seniors who were all accepted to college with great financial aid packages,” De Lucca said. That includes University of California, Berkeley and UCLA, some of the top colleges in their area. “That’s a huge success.”

While Mullen said it’s unknown if the program will continue or expand, HUD is studying its performance right now. De Lucca and Hyman said the program could be mirrored in other cities with local support.

“The great thing is, it’s so adaptive,” Hyman said.

Parental involvement is important to success in college

Rachel Gonzalez, director of training and capacity building at Los Angeles-based Families in Schools, still remembers the day in second grade when her dad sat her and her siblings down. He had just come home from one of his four jobs where he was working a graveyard shift as a high school janitor.

He said: “You are not going to do this. Where are you going to college?”

That stuck with Gonzalez and her siblings. They all went to college and two earned master’s degrees. They gave those diplomas to their parents as recognition for what they sacrificed for them.

Rachel Gonzalez, director of training and capacity building at Los Angeles-based Families in Schools, talks about the importance of engaging parents in all communities in order for students to excel in secondary education.

(Photo by Stephanie Hacke/PublicSource)Every parent has a dream for their child, Gonzalez told a group attending a workshop at NCAN this week. It’s up to educators to make sure they’re providing opportunities for parents to engage with their child’s education, she said.

“Parents and school staff should be equal partners,” she said. “It does take work. It’s not easy all the time, but it’s worth it.”

There’s no one-size-fits-all for what parent engagement looks like. In every community, it’s different based on the needs of the area and the people living there, Gonzalez said. Adapt to that.

“It’s important to remember that there are strengths in every family,” she said.

Attendees talked about how family engagement looks different in their communities. One mentioned that in Chicago, they refer to it as “parent/family” involvement because you can’t assume that a parent is always the one raising a child.

Others pointed to the refugee populations they work with and how culture plays a major role when interacting with families.

Tremayne Horne, a family learning navigator at the Children’s Museum in Indianapolis, talked about a student he was working with who was on track to go to college when she suddenly “dropped off the grid.” Her home was constantly being burglarized. Her family couldn’t focus on college, when they weren’t safe.

He worked with community partners to get the student and her family into a safe place to live, so she could focus on preparing for college. Having partners who can help families with other aspects of their lives they might be struggling with is vital, Horne said.

Gonzalez said it’s always important to use a language parents understand and feel comfortable with — whether that’s arranging communication in a foreign language or ensuring that the information isn’t being presented in a jargony way; parents need to know what they’re hearing is important for them.

Parents supporting a child’s college or career readiness plays a huge role in the child’s success, she said. To work with families, you need to meet them where they are.

“Learn what works for you and your families,” Gonzalez said.

Clinton Wilson, the supervisor of high school counseling at Guilford County Schools in Greensboro, North Carolina, said his counselors visit community centers, so parents don’t have to take a bus to meet with them.

“We have to step outside our comfort zone, so they don’t step outside of their comfort zone,” he said.

Stephanie Hacke is a freelance journalist in Pittsburgh. She can be reached at stephanie.hacke@gmail.com or on Twitter at @StephOnRecord.

This project has been made possible with the generous support of The Grable Foundation and the Education Writers Association.