Part of the PublicSource series

Failing the Future

The South Fayette School District is proud of its “STEAM Story.” In a district video, educators gently guide first graders using magnetic circuitry kits, fourth graders working with LEGO robots and seventh graders creating their own Smartphone apps.

The video shows a student making musical notes by tapping a piece of cardboard connected to a computer, a group creating safety updates to a walker for the elderly and another student building a basketball trivia app. One young student featured in the video says, “I really like this technology because you get to make stuff out of it and it comes out really cool at the end.”

Similarly, the Fox Chapel Area School District shares a video that features its mobile fabrication lab and stories about students using 3D printers, vinyl cutters and computerized milling CNC machines.

And, in the Upper St Clair School District, the website announces that a group of middle and elementary school students are winners of a multimedia excellence award at the September World Artificial Intelligence Competition at Carnegie Mellon University.

In the world of STEAM, it’s easy to get left behind if your school district struggles financially.

Educators throughout the region will tell you that access to Science, Technology, Engineering Art and Math [STEAM] curriculum and activities are an essential part of today’s education. They teach students how to think critically, take risks, bounce back from failure and strategize as a member of a working group — all skills necessary in the 21st century workplace.

But providing those experiences often requires the purchase of expensive equipment and cutting-edge technology and the funds to provide professional development to teachers.

Well-resourced districts are forging ahead — creating makerspaces and purchasing or building fabrication labs equipped with STEAM tools, virtual reality spaces and even an artificial intelligence lab like the one opening at David E. Williams Middle School in the Montour School District this fall.

In the world of STEAM, it’s easy to get left behind if your school district struggles financially.

STEAM equipment is expensive, with items ranging from several hundred to several thousand dollars.

The interior of Kelly Elementary school located in Wilkinsburg.

(Photo by Kat Procyk/PublicSource)In districts where budgets are stretched to provide even the basics, the creation of well-equipped STEAM labs and makerspaces can — and often do — end up on the wish list.

“There is no brilliance gap. The kids in these districts have incredible talents,” said Sunanna Chand, executive director of Remake Learning. “We fundamentally believe a change in the way learning looks and feels should not be a luxury or be relegated to people who can afford it.”

Private funding sources are closing part of the gap.

For example, in the Aliquippa School District, which is on the state’s financial watch list, Superintendent Peter Carbone said there is no STEAM curriculum, no makerspaces and no one-to-one technology for students, which would provide students with personal iPads or Chromebooks as in other districts.

But funding from Highmark and the Beaver County Educational Trust paid for a one-day “STEAM walk” at Aliquippa Elementary in May. The walk allowed students to visit various stations to work on STEAM projects.

In the Wilkinsburg School District, which is also on the state’s financial watch list, makerspaces have been created at the district’s two elementary schools through a $16,500 Catalyst grant awarded in the 2017-18 school year by the Allegheny Intermediate Unit [AIU], a regional public school service agency. The district received a second grant this school year.

“We fundamentally believe a change in the way learning looks and feels should not be a luxury or be relegated to people who can afford it.”

Sto-Rox School District also used a Catalyst grant to create a STEAM curriculum at the junior-senior high school and to enhance one started the previous year at the Primary Center and Upper Elementary School with a grant from the Ohio River Consortium.

The Catalyst grants are funded by the Grable and Hillman foundations*. Past AIU STEAM grants have also been funded in part by Chevron.

The Duquesne City School District has used multiple grants from AIU and other sources to create two makerspaces and revamp the library into a video production area.

The AIU has awarded STEAM grants for nearly a decade, but in 2017-18, it reserved the program specifically for districts with high percentages of students qualifying for free or reduced lunches.

In addition to Sto-Rox, Wilkinsburg and Duquesne, grants went to Clairton, Monessen and New Castle.

Support and training for STEAM

Along with the grant money, the districts got yearlong professional support from the AIU’s Center for Creativity. Tyler Samstag, who heads the center and serves as the AIU director of instructional innovation, teaching and learning, helped district representatives avoid mistakes and “strategize what kinds of support [they] need.”

A common mistake in under-resourced districts is to purchase expensive equipment and not know how to use it or how to incorporate it into classroom lessons, Samstag said.

“You can’t just buy a 3D printer and print,” Samstag said. “You need to understand it.”

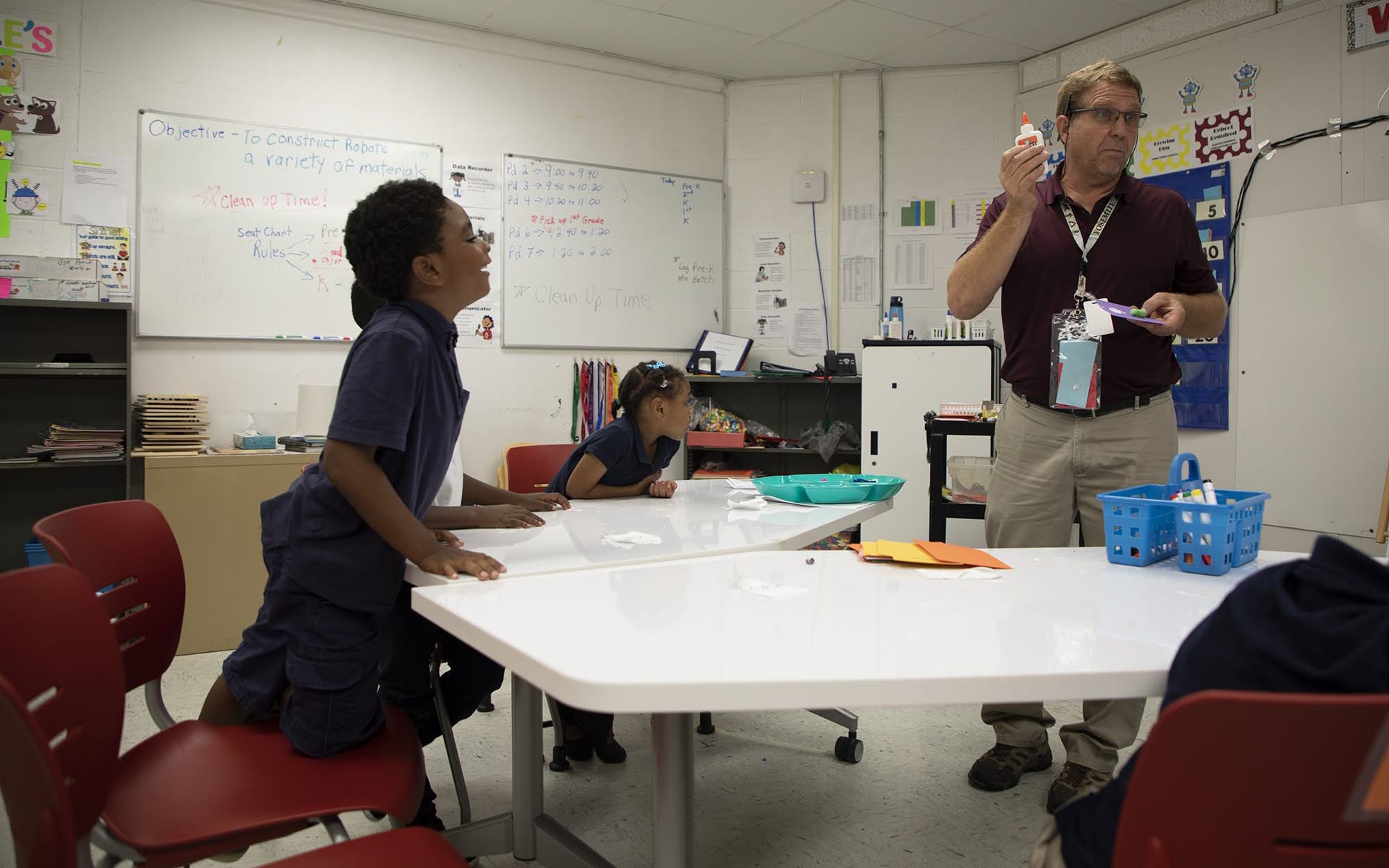

At the March meeting of the Catalyst grant district representatives, it appeared that teachers and administrators were starting their programs with free software and low-cost supplies and equipment. Some of the projects discussed could be created out of materials found at flea markets.

In Wilkinsburg, elementary teacher Russell Bush built homemade marble runs that he said created excitement among his students. Students learned the mechanics of motion by watching how objects of different sizes and volumes traveled through the maze. One challenge Bush said he issued was to make a marble go as slowly as possible by including curves and obstacles in the track.

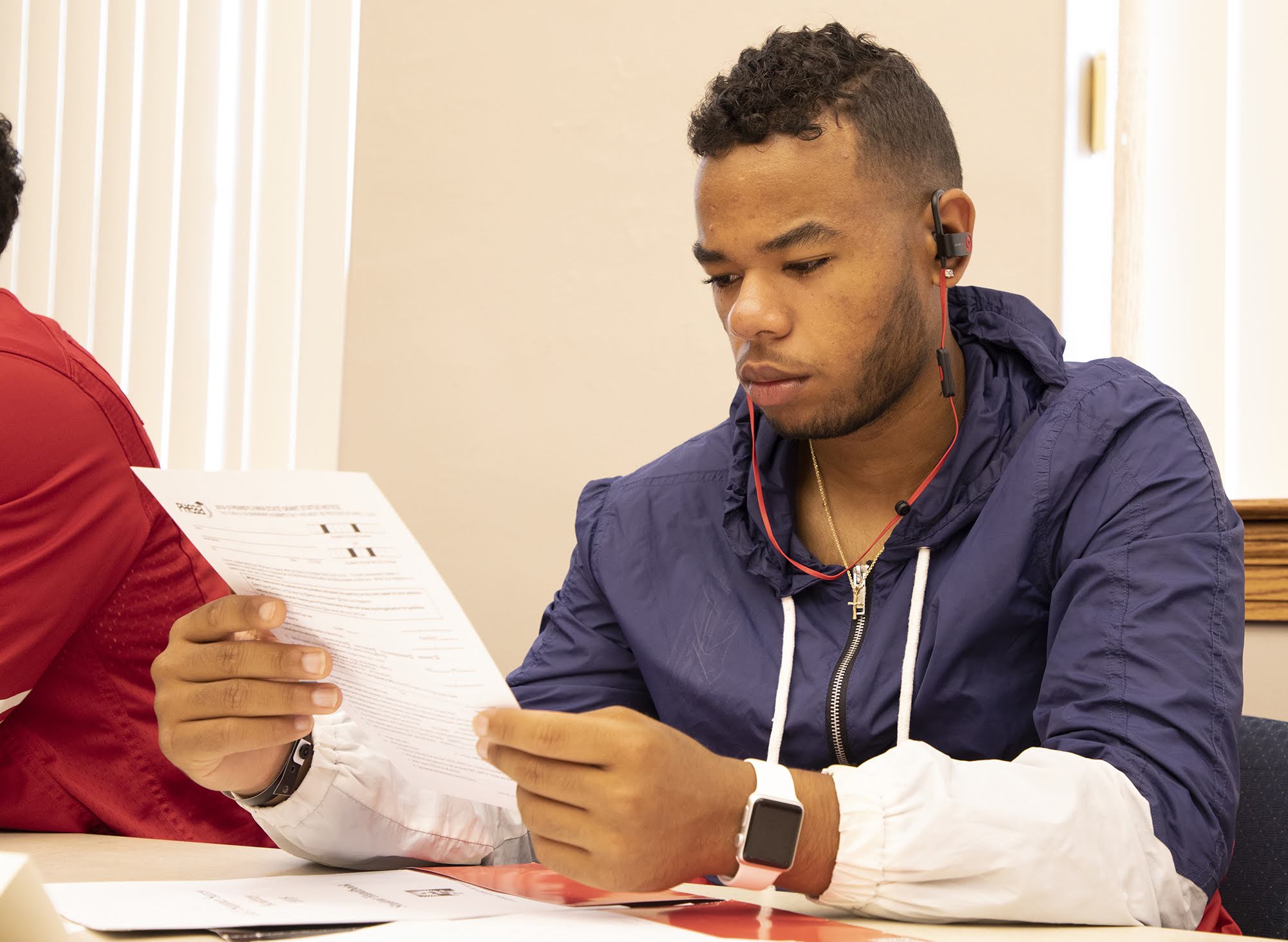

Russell Bush leads a first-grade class at Kelly Elementary in Wilkinsburg. For his STEAM class lesson, Bush had the students build robots out of construction paper and other materials. (Photo by Kat Procyk/PublicSource)

Bush told the story of a student who was often disruptive in class until he had a chance to work with the marble run. “He wouldn’t leave the room. Now he calms down and likes to learn,” Bush said.

The Wilkinsburg district has created makerspaces at each of its two elementary buildings with the grant money. The district received a second Catalyst grant for the 2018-19 school year.

“The real bright light in all of this is our kids are mesmerized in this environment. They are exposed to a type of learning they have not experienced before. The ability to manipulate tools and construct and deconstruct,” said Cathleen Cubelic, assistant to the superintendent in Wilkinsburg.

Cubelic said the grant money was key to creating the STEAM curriculum and makerspaces.

“Absolutely we couldn’t do any of that with just the resources at our disposal,” she said.

One frustration with the program is that the district has funds to send its teachers to other districts with more advanced STEAM programs for professional development, but Wilkinsburg cannot get substitute teachers to come to the district.

“The district has a reputation that scares people away. It’s hindering our ability to fully realize and really implement the resources that have been provided to us,” Cubelic said.

In Clairton, the STEAM program consists of low-cost items placed on carts that can be brought into the classroom. Teachers there said there was no available space for a STEAM lab or makerspace in the single district building that houses grades K-12.

In addition to the professional development that came with the Catalyst grant, some Clairton teachers sought free professional development in June from the Pittsburgh FAB Institute at Elizabeth Forward High School.

“Free is good,” said Sally Kunkel, a fourth-grade teacher at Clairton Elementary.

She spent one morning of the training program learning how to create a magnet with the Clairton Bears logo on it. She designed it on a laptop, using free Inkscape graphics software. A laser cutter etched the design into wood, which was then attached to a magnet.

Kunkel is new to the maker movement. Clairton hasn’t been able to afford professional development or the equipment. At the Elizabeth Forward training, she learned how to incorporate maker projects into her lessons by using free software and low-cost materials like nuts, bolts and wires. She and a colleague used the materials to design a butterfly and a bee.

Sally Kunkel (left), a teacher at the Clairton School District, laughs with her sister, Wendy Pasternack, also a teacher at the Elizabeth Forward School District, after feeding paper into the vinyl cutter at the FAB Institute at Elizabeth Forward High School on June 21.

(Photo by Kat Procyk/PublicSource)Kunkel said she envisioned using the project to combine lessons in art and science.

In addition to attending free professional development, Kunkel also borrows STEAM equipment from the lending libraries of the AIU and The Education Partnership.

Sto-Rox faculty members Julie Himmelstein, a librarian who teaches video production, and Tim Hinkle, who teaches technology education, also learned ideas for maker projects at the Elizabeth Forward training.

As with the Clairton teachers, Himmelstein and Hinkle have to adjust what they learned to the materials and budget they have at Sto-Rox. The district received a second $16,500 Catalyst grant for the 2018-19 school year.

“We come back with ideas from this that we have to scale back, but we are making connections with other districts, hearing other people’s projects and ideas,” Himmelstein said.

Himmelstein said getting students to work with hands-on STEAM projects teaches important lessons like the ability to fail and then correct mistakes. Students at Sto-Rox often resist stepping out of their comfort zones, she said.

“They are not so interested in putting themselves out there,” Himmelstein said. “We need for them to show they can step out and show they can do the same things as other kids.”

The Duquesne City School District, which is in financial recovery and led by a state receiver, has been successful in obtaining multiple grants for STEAM projects in recent years.

“We need for them to show they can step out and show they can do the same things as other kids.”

In the past four school years, the AIU has awarded the district grants for STEAM projects, totaling $73,000.

The funding allowed the district, which holds grades PreK-6 at Duquesne Elementary, to create two STEAM areas, add a multimedia area to its library and, for the 2018-19 school year, start a coding and robotics lab.

The Creation Station for grades PreK-2 features LEGOs as well as water and sand tables. The Boiler Room, for grades 3-5, is equipped similar to a science lab but also has virtual reality goggles purchased with a $5,000 grant from The Sprout Fund. Students were using the goggles last May during a unit on the Holocaust to take a virtual tour of the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C.

“For Duquesne, that would be a difficult task for someone to go to our board or [state receiver] Paul Rach and say, ‘Hey listen, would you be willing to put $20,000 into a makerspace?” said Stan Whiteman, director of curriculum, instruction, assessment and technology. “We have greater needs in our building that would need to be addressed.”

Mobile fab labs

While grant money has helped financially-strapped districts jumpstart STEAM programs with low-cost materials, finding ways to buy expensive equipment such as 3D printers, vinyl and laser cutters and CNC machines remains a challenge.

That problem has been addressed in Fayette, Green and Washington counties through a mobile fabrication lab, operated by Intermediate Unit 1.

The lab holds a laser engraver, 3D printer, vinyl cutter and CNC milling machine — a wood cutter with a computer-aided design program. The mobile fab lab travels to small rural districts that can’t afford to provide the equipment for students.

The Benedum Foundation and Chevron funded the fab lab with $200,000.

Teachers in districts that use the lab receive professional development training from Intermediate Unit 1 and submit lesson plans before the lab is sent to their schools, said Charles Mahoney, the intermediate unit’s executive director.

During a June 12 tour of the fab lab, state Secretary of Education Pedro Rivera called the mobile lab “a gem” for its ability to bring STEAM education to students whose districts can’t afford their own programs.

In Allegheny County, the Fox Chapel Area School District has a mobile fab lab built into a tiny house structure. High school engineering students created plans for the structure. A district truck tows the lab; it has a generator or can be hooked up to a power source. The district received grant money from the Grable Foundation, lumber donated by 84 Lumber and used district funds to create the lab.

The district uses the lab for Fox Chapel students and shares with districts that have fewer resources, said Megan Cicconi, executive director of instructional and innovative leadership for the district.

They take the lab on visits to the New Kensington-Arnold School District and Mary Queen of Apostles School, both in Westmoreland County, and Allegheny Valley and Shaler Area schools in Allegheny County.

“Our school board could have said, ‘No, it will cost us money to help others.’ But they didn’t,” Cicconi said. “It should be part of what we do to help each other.”

*PublicSource receives funding from the Hillman and Grable foundations.

Mary Niederberger covers education for PublicSource. She can be reached at 412-515-0064 or mary@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by J. Dale Shoemaker.

This project has been made possible with the generous support of The Grable Foundation and the Education Writers Association.